In the last few years of total hip arthroplasty, acetabular component orientation has become one of the most controversial topics. Safe zones for cup position were created to help guide surgeons in reducing complications such as dislocation.1 Overcoming intraoperative patient movement is key to maintaining these safe zones.

Lewinnek’s now infamous paper from 19781 which set the first guideline was revisited by Callanan’s group in 20112 and both have fallen from a gold standard paper & Charnley award-winning pedestal to being viewed as almost medical malpractice in recent publications.3,4

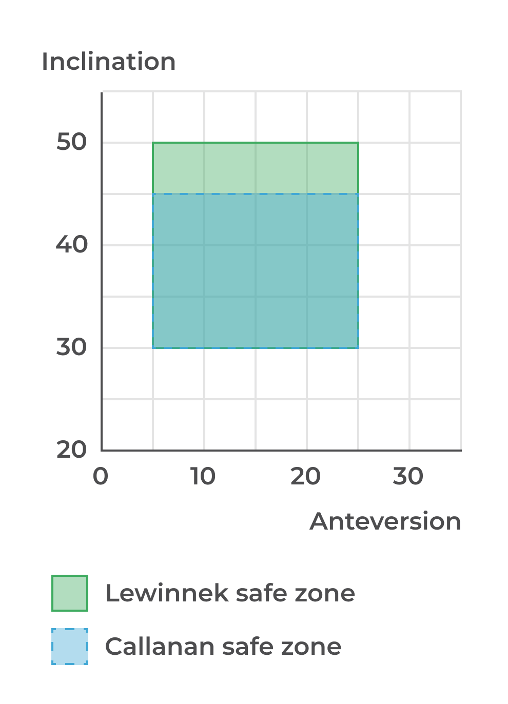

| Inclination | Anteversion | |

| Lewinnek et al. 19781 | 40° +/- 10° | 15° +/- 10° |

| Callanan et al. 20112 | 40° + 5°/- 10° | 15° +/- 10° |

These ‘safe zones’ can still offer some boundaries to work within and perhaps now indicate a ‘tread with caution’ approach to being outside of them.

Problem of consistency

Whether surgeons choose this framework or something more tailored to a single patient’s anatomy, we still need to consider the problem of consistently hitting the surgeon’s preferred component orientation. So we can at least leverage the fact these ‘safe zones’ are widely published to help illustrate the problem of consistency.

A quick literature review can show that Lewinnek’s zone is missed between 20 – 30% of the time5,6 and Callanan’s between 38 – 62% of the time.2,6,7 With target ranges of 20° and still a reasonably high chance of missing, what happens to our accuracy and precision as we move to this new paradigm of targets where a consistent 40° / 20° is desired or a variable, functional target derived from a hip-spine work up?

I think the answer is obvious – that both accuracy & precision will decrease – but why?

Decrease in accuracy and precision

Dr. Peter Sculco, a leading hip and knee replacement surgeon at the Hospital for Special Surgery helped outline a few reasons for this including the inability to see internal landmarks due to

- Smaller incisions,

- Exposure issues, and

- High BMI patients

He also noted that even when you can see these landmarks, that they may have a unique acetabular morphology including:

- Lack visibility of the transverse acetabular ligament, and

- Osteophytes covering the true acetabulum.

In addition to these internal landmark difficulties, external landmarks can be affected by intraoperative patient movement.

Intraoperative patient movement

Intraoperative patient movement is a well-documented, common occurrence in total hip arthroplasty and perhaps a significant contributor to the lack of consistent component orientation in literature.8-11

So what is it?

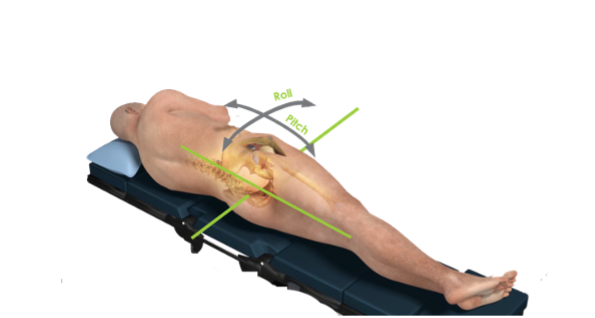

Intraoperative patient movement can be broken into two major components:

- Patient Roll

- Rotation of the body and pelvis in the transverse plane of the patient – ie. the patient rolling towards prone or supine

- Patient Pitch / Obliquity

- Rotation of the pelvis in the coronal plane of the patient – ie. the movement of the inter-ASIS or interischial line away from vertical

Intellijoint HIP® has the ability to track these movements due to our camera being fixed to the patient’s pelvis. Between our research and previously published data we know that:

- 1 in 4 patients roll greater than 10°8 with an average roll of 14.5°11 and,

- 1 in 5 patients pitch greater than 4°8

- These values are independent of surgeon, BMI, sex & pre-op ROM10

These numbers show a high rate of occurrence for substantial movement. But how does this translate into component orientation?

The relationship was determined through simulation that 1° of Roll equates to 0.64° of Anteversion and -0.20° of Inclination and that 1° of Pitch equates to 1° of Inclination.12 It’s also important to note that there is a bias to the direction of this movement in a lateral decubitus positioned patient – in roll it’s anteriorly and in pitch, it’s towards the head.10

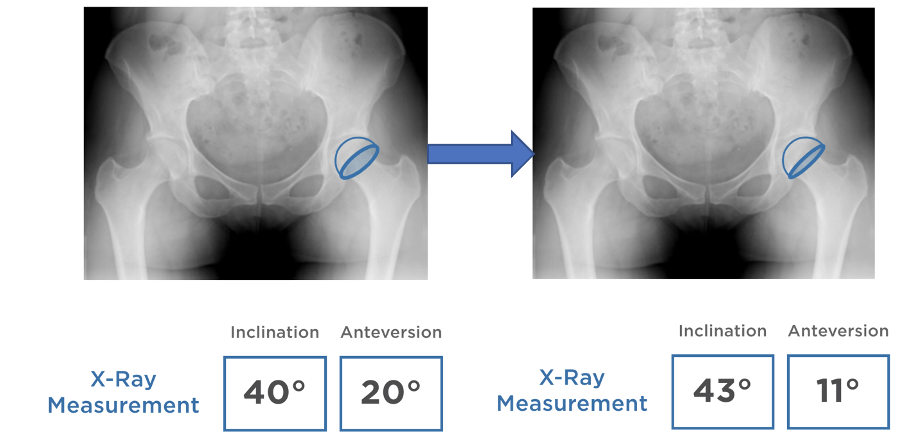

So in simpler terms – that average roll of 14.5° becomes 9.3° of underestimated Anteversion and 2.9° of overestimated Inclination and a 40° / 20° quickly becomes a 43° / 11° and a surprise on the post-op.

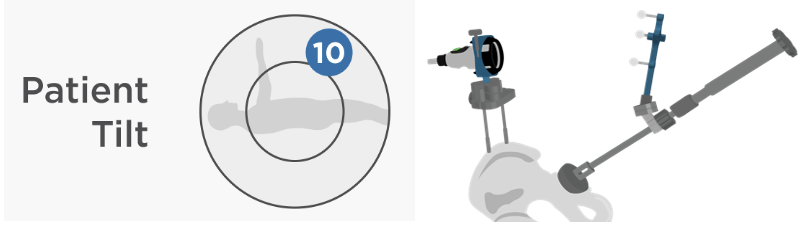

Intellijoint HIP® makes it easy to assess patient movement via a Patient Tilt Monitor built into the software and account for it throughout a case so you don’t get caught off guard in a case like this. Our Universal V-Block can attach to any acetabular inserter and provide real-time quantitative data with any patient movement accounted for by the navigation system.

This makes our open-platform, easy-to-use, computer-assisted navigation system uniquely poised to provide a more consistent acetabular orientation by removing known barriers to missing your target preference.

1 Lewinnek GE, Lewis JL, Tarr R, Compere CL, Zimmerman JR. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978 Mar;60(2):217-20. PMID: 641088.

2 Callanan MC, Jarrett B, Bragdon CR, Zurakowski D, Rubash HE, Freiberg AA, Malchau H. The John Charnley Award: risk factors for cup malpositioning: quality improvement through a joint registry at a tertiary hospital. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 Feb;469(2):319-29. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1487-1. PMID: 20717858; PMCID: PMC3018230.

3 Dorr LD, Callaghan JJ. Death of the Lewinnek "Safe Zone". J Arthroplasty. 2019 Jan;34(1):1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.10.035. PMID: 30527340.

4 Abdel MP, von Roth P, Jennings MT, Hanssen AD, Pagnano MW. What Safe Zone? The Vast Majority of Dislocated THAs Are Within the Lewinnek Safe Zone for Acetabular Component Position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016 Feb;474(2):386-91. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4432-5. PMID: 26150264; PMCID: PMC4709312

5 Bosker BH, Verheyen CC, Horstmann WG, Tulp NJ. Poor accuracy of freehand cup positioning during total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007 Jul;127(5):375-9. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0294-y. Epub 2007 Feb 13. PMID: 17297597; PMCID: PMC1914284.

6 Domb BG, El Bitar YF, Sadik AY, Stake CE, Botser IB. Comparison of robotic-assisted and conventional acetabular cup placement in THA: a matched-pair controlled study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Jan;472(1):329-36. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3253-7. Epub 2013 Aug 29. PMID: 23990446; PMCID: PMC3889439.

7 Barrack RL, Krempec JA, Clohisy JC, McDonald DJ, Ricci WM, Ruh EL, Nunley RM. Accuracy of acetabular component position in hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Oct 2;95(19):1760-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01704. PMID: 24088968.

8 Schwarzkopf R, Muir JM, Paprosky WG, Seymour S, Cross MB, Vigdorchik JM. Quantifying Pelvic Motion During Total Hip Arthroplasty Using a New Surgical Navigation Device. J Arthroplasty. 2017 Oct;32(10):3056-3060. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.04.046. Epub 2017 May 4. PMID: 28559196.

9 Grammatopoulos G, Pandit HG, da Assunção R, Taylor A, McLardy-Smith P, De Smet KA, Murray DW, Gill HS. Pelvic position and movement during hip replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014 Jul;96-B(7):876-83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B7.32107. PMID: 24986939.

10 Gonzalez Della Valle A, Shanaghan K, Benson JR, Carroll K, Cross M, McLawhorn A, Sculco PK. Pelvic pitch and roll during total hip arthroplasty performed through a posterolateral approach. A potential source of error in free-hand cup positioning. Int Orthop. 2019 Aug;43(8):1823-1829. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4141-2. Epub 2018 Sep 21. PMID: 30242516.

11 Asayama I, Akiyoshi Y, Naito M, Ezoe M. Intraoperative pelvic motion in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004 Dec;19(8):992-7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.03.013. PMID: 15586335.

12 Vigdorchik J, Muir, JM, Buckland, A, Elbuluk, AM, Alguire, A, Schipper, J, Schwarzkopf, R. Undetected intraoperative pelvic movement can lead to inaccurate acetabular cup component placement during total hip arthroplasty: A mathematical simulation estimating change in cup position. Journal of Hip Surgery. 2017;1(4):7.